Form of orthodontics

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Dental braces" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

Dental braces

Dental braces

Dental braces (also known as orthodontic braces, or simply braces) are devices used in orthodontics that align and straighten teeth and help position them with regard to a person's bite, while also aiming to improve dental health. They are often used to correct underbites, as well as malocclusions, overbites, open bites, gaps, deep bites, cross bites, crooked teeth, and various other flaws of the teeth and jaw. Braces can be either cosmetic or structural. Dental braces are often used in conjunction with other orthodontic appliances to help widen the palate or jaws and to otherwise assist in shaping the teeth and jaws.

Process

[edit]

The application of braces moves the teeth as a result of force and pressure on the teeth. Traditionally, four basic elements are used: brackets, bonding material, arch wire, and ligature elastic (also called an "O-ring"). The teeth move when the arch wire puts pressure on the brackets and teeth. Sometimes springs or rubber bands are used to put more force in a specific direction.[1]

Braces apply constant pressure which, over time, moves teeth into the desired positions. The process loosens the tooth after which new bone grows to support the tooth in its new position. This is called bone remodelling. Bone remodelling is a biomechanical process responsible for making bones stronger in response to sustained load-bearing activity and weaker in the absence of carrying a load. Bones are made of cells called osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Two different kinds of bone resorption are possible: direct resorption, which starts from the lining cells of the alveolar bone, and indirect or retrograde resorption, which occurs when the periodontal ligament has been subjected to an excessive amount and duration of compressive stress.[2] Another important factor associated with tooth movement is bone deposition. Bone deposition occurs in the distracted periodontal ligament. Without bone deposition, the tooth will loosen, and voids will occur distal to the direction of tooth movement.[3]

Types

[edit]

"Clear" braces

"Clear" braces

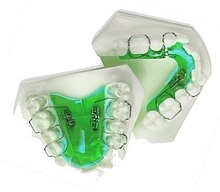

Upper and Lower Jaw Functional Expanders

Upper and Lower Jaw Functional Expanders

- Traditional metal wired braces (also known as "train track braces") are stainless-steel and are sometimes used in combination with titanium. Traditional metal braces are the most common type of braces.[4] These braces have a metal bracket with elastic ties (also known as rubber bands) holding the wire onto the metal brackets. The second-most common type of braces is self-ligating braces, which have a built-in system to secure the archwire to the brackets and do not require elastic ties. Instead, the wire goes through the bracket. Often with this type of braces, treatment time is reduced, there is less pain on the teeth, and fewer adjustments are required than with traditional braces.

- Gold-plated stainless steel braces are often employed for patients allergic to nickel (a basic and important component of stainless steel), but may also be chosen for aesthetic reasons.

- Lingual braces are a cosmetic alternative in which custom-made braces are bonded to the back of the teeth making them externally invisible.

- Titanium braces resemble stainless-steel braces but are lighter and just as strong. People with allergies to nickel in steel often choose titanium braces, but they are more expensive than stainless steel braces.

- Customized orthodontic treatment systems combine high technology including 3-D imaging, treatment planning software and a robot to custom bend the wire. Customized systems such as this offer faster treatment times and more efficient results.[5]

- Progressive, clear removable aligners may be used to gradually move teeth into their final positions. Aligners are generally not used for complex orthodontic cases, such as when extractions, jaw surgery, or palate expansion are necessary.[medical citation needed][6]

Fitting procedure

[edit]

A patient's teeth are prepared for the application of braces.

A patient's teeth are prepared for the application of braces.

Orthodontic services may be provided by any licensed dentist trained in orthodontics. In North America, most orthodontic treatment is done by orthodontists, who are dentists in the diagnosis and treatment of malocclusions—malalignments of the teeth, jaws, or both. A dentist must complete 2–3 years of additional post-doctoral training to earn a specialty certificate in orthodontics. There are many general practitioners who also provide orthodontic services.

The first step is to determine whether braces are suitable for the patient. The doctor consults with the patient and inspects the teeth visually. If braces are appropriate, a records appointment is set up where X-rays, moulds, and impressions are made. These records are analyzed to determine the problems and the proper course of action. The use of digital models is rapidly increasing in the orthodontic industry. Digital treatment starts with the creation of a three-dimensional digital model of the patient's arches. This model is produced by laser-scanning plaster models created using dental impressions. Computer-automated treatment simulation has the ability to automatically separate the gums and teeth from one another and can handle malocclusions well; this software enables clinicians to ensure, in a virtual setting, that the selected treatment will produce the optimal outcome, with minimal user input.[medical citation needed]

Typical treatment times vary from six months to two and a half years depending on the complexity and types of problems. Orthognathic surgery may be required in extreme cases. About 2 weeks before the braces are applied, orthodontic spacers may be required to spread apart back teeth in order to create enough space for the bands.

Teeth to be braced will have an adhesive applied to help the cement bond to the surface of the tooth. In most cases, the teeth will be banded and then brackets will be added. A bracket will be applied with dental cement, and then cured with light until hardened. This process usually takes a few seconds per tooth. If required, orthodontic spacers may be inserted between the molars to make room for molar bands to be placed at a later date. Molar bands are required to ensure brackets will stick. Bands are also utilized when dental fillings or other dental works make securing a bracket to a tooth infeasible. Orthodontic tubes (stainless steel tubes that allow wires to pass through them), also known as molar tubes, are directly bonded to molar teeth either by a chemical curing or a light curing adhesive. Usually, molar tubes are directly welded to bands, which is a metal ring that fits onto the molar tooth. Directly bonded molar tubes are associated with a higher failure rate when compared to molar bands cemented with glass ionomer cement. Failure of orthodontic brackets, bonded tubes or bands will increase the overall treatment time for the patient. There is evidence suggesting that there is less enamel decalcification associated with molar bands cemented with glass ionomer cement compared with orthodontic tubes directly cemented to molars using a light cured adhesive. Further evidence is needed to withdraw a more robust conclusion due to limited data.[7]

An archwire will be threaded between the brackets and affixed with elastic or metal ligatures. Ligatures are available in a wide variety of colours, and the patient can choose which colour they like. Arch wires are bent, shaped, and tightened frequently to achieve the desired results.

Dental braces, with a transparent power chain, removed after completion of treatment.

Dental braces, with a transparent power chain, removed after completion of treatment.

Modern orthodontics makes frequent use of nickel-titanium archwires and temperature-sensitive materials. When cold, the archwire is limp and flexible, easily threaded between brackets of any configuration. Once heated to body temperature, the arch wire will stiffen and seek to retain its shape, creating constant light force on the teeth.

Brackets with hooks can be placed, or hooks can be created and affixed to the arch wire to affix rubber bands. The placement and configuration of the rubber bands will depend on the course of treatment and the individual patient. Rubber bands are made in different diameters, colours, sizes, and strengths. They are also typically available in two versions: Coloured or clear/opaque.

The fitting process can vary between different types of braces, though there are similarities such as the initial steps of moulding the teeth before application. For example, with clear braces, impressions of a patient's teeth are evaluated to create a series of trays, which fit to the patient's mouth almost like a protective mouthpiece. With some forms of braces, the brackets are placed in a special form that is customized to the patient's mouth, drastically reducing the application time.

In many cases, there is insufficient space in the mouth for all the teeth to fit properly. There are two main procedures to make room in these cases. One is extraction: teeth are removed to create more space. The second is expansion, in which the palate or arch is made larger by using a palatal expander. Expanders can be used with both children and adults. Since the bones of adults are already fused, expanding the palate is not possible without surgery to separate them. An expander can be used on an adult without surgery but would be used to expand the dental arch, and not the palate.

Sometimes children and teenage patients, and occasionally adults, are required to wear a headgear appliance as part of the primary treatment phase to keep certain teeth from moving (for more detail on headgear and facemask appliances see Orthodontic headgear). When braces put pressure on one's teeth, the periodontal membrane stretches on one side and is compressed on the other. This movement needs to be done slowly or otherwise, the patient risks losing their teeth. This is why braces are worn as long as they are and adjustments are only made every so often.

Young Colombian man during an adjustment visit for his orthodontics

Young Colombian man during an adjustment visit for his orthodontics

Braces are typically adjusted every three to six weeks. This helps shift the teeth into the correct position. When they get adjusted, the orthodontist removes the coloured or metal ligatures keeping the arch wire in place. The arch wire is then removed and may be replaced or modified. When the archwire has been placed back into the mouth, the patient may choose a colour for the new elastic ligatures, which are then affixed to the metal brackets. The adjusting process may cause some discomfort to the patient, which is normal.

Post-treatment

[edit]

Patients may need post-orthodontic surgery, such as a fiberotomy or alternatively a gum lift, to prepare their teeth for retainer use and improve the gumline contours after the braces come off. After braces treatment, patients can use a transparent plate to keep the teeth in alignment for a certain period of time. After treatment, patients usually use transparent plates for 6 months. In patients with long and difficult treatment, a fixative wire is attached to the back of the teeth to prevent the teeth from returning to their original state.[8]

Retainers

[edit]

Main article: Retainer (orthodontic device)

Hawley retainers are the most common type of retainers. This picture shows retainers for the top (right) and bottom (left) of the mouth.

Hawley retainers are the most common type of retainers. This picture shows retainers for the top (right) and bottom (left) of the mouth.

In order to prevent the teeth from moving back to their original position, retainers are worn once the treatment is complete. Retainers help in maintaining and stabilizing the position of teeth long enough to permit the reorganization of the supporting structures after the active phase of orthodontic therapy. If the patient does not wear the retainer appropriately and/or for the right amount of time, the teeth may move towards their previous position. For regular braces, Hawley retainers are used. They are made of metal hooks that surround the teeth and are enclosed by an acrylic plate shaped to fit the patient's palate. For Clear Removable braces, an Essix retainer is used. This is similar to the original aligner; it is a clear plastic tray that is firmly fitted to the teeth and stays in place without a plate fitted to the palate. There is also a bonded retainer where a wire is permanently bonded to the lingual side of the teeth, usually the lower teeth only.

Headgear

[edit]