Correctional branch of dentistry

Orthodontics

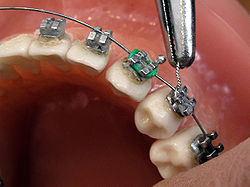

Connecting the arch-wire on brackets with wire

|

| Names |

Orthodontist |

|

Occupation type

|

Specialty |

|

Activity sectors

|

Dentistry |

|

Education required

|

Dental degree, specialty training |

|

Fields of

employment

|

Private practices, hospitals |

Orthodontics[a][b] is a dentistry specialty that addresses the diagnosis, prevention, management, and correction of mal-positioned teeth and jaws, as well as misaligned bite patterns.[2] It may also address the modification of facial growth, known as dentofacial orthopedics.

Abnormal alignment of the teeth and jaws is very common. The approximate worldwide prevalence of malocclusion was as high as 56%.[3] However, conclusive scientific evidence for the health benefits of orthodontic treatment is lacking, although patients with completed treatment have reported a higher quality of life than that of untreated patients undergoing orthodontic treatment.[4][5] The main reason for the prevalence of these malocclusions is diets with less fresh fruit and vegetables and overall softer foods in childhood, causing smaller jaws with less room for the teeth to erupt.[6] Treatment may require several months to a few years and entails using dental braces and other appliances to gradually adjust tooth position and jaw alignment. In cases where the malocclusion is severe, jaw surgery may be incorporated into the treatment plan. Treatment usually begins before a person reaches adulthood, insofar as pre-adult bones may be adjusted more easily before adulthood.

History

[edit]

Though it was rare until the Industrial Revolution,[7] there is evidence of the issue of overcrowded, irregular, and protruding teeth afflicting individuals. Evidence from Greek and Etruscan materials suggests that attempts to treat this disorder date back to 1000 BC, showcasing primitive yet impressively well-crafted orthodontic appliances. In the 18th and 19th centuries, a range of devices for the "regulation" of teeth were described by various dentistry authors who occasionally put them into practice.[8] As a modern science, orthodontics dates back to the mid-1800s.[9] The field's influential contributors include Norman William Kingsley[9] (1829–1913) and Edward Angle[10] (1855–1930). Angle created the first basic system for classifying malocclusions, a system that remains in use today.[9]

Beginning in the mid-1800s, Norman Kingsley published Oral Deformities, which is now credited as one of the first works to begin systematically documenting orthodontics. Being a major presence in American dentistry during the latter half of the 19th century, not only was Kingsley one of the early users of extraoral force to correct protruding teeth, but he was also one of the pioneers for treating cleft palates and associated issues. During the era of orthodontics under Kingsley and his colleagues, the treatment was focused on straightening teeth and creating facial harmony. Ignoring occlusal relationships, it was typical to remove teeth for a variety of dental issues, such as malalignment or overcrowding. The concept of an intact dentition was not widely appreciated in those days, making bite correlations seem irrelevant.[8]

In the late 1800s, the concept of occlusion was essential for creating reliable prosthetic replacement teeth. This idea was further refined and ultimately applied in various ways when dealing with healthy dental structures as well. As these concepts of prosthetic occlusion progressed, it became an invaluable tool for dentistry.[8]

It was in 1890 that the work and impact of Dr. Edwards H. Angle began to be felt, with his contribution to modern orthodontics particularly noteworthy. Initially focused on prosthodontics, he taught in Pennsylvania and Minnesota before directing his attention towards dental occlusion and the treatments needed to maintain it as a normal condition, thus becoming known as the "father of modern orthodontics".[8]

By the beginning of the 20th century, orthodontics had become more than just the straightening of crooked teeth. The concept of ideal occlusion, as postulated by Angle and incorporated into a classification system, enabled a shift towards treating malocclusion, which is any deviation from normal occlusion.[8] Having a full set of teeth on both arches was highly sought after in orthodontic treatment due to the need for exact relationships between them. Extraction as an orthodontic procedure was heavily opposed by Angle and those who followed him. As occlusion became the key priority, facial proportions and aesthetics were neglected. To achieve ideal occlusals without using external forces, Angle postulated that having perfect occlusion was the best way to gain optimum facial aesthetics.[8]

With the passing of time, it became quite evident that even an exceptional occlusion was not suitable when considered from an aesthetic point of view. Not only were there issues related to aesthetics, but it usually proved impossible to keep a precise occlusal relationship achieved by forcing teeth together over extended durations with the use of robust elastics, something Angle and his students had previously suggested. Charles Tweed[11] in America and Raymond Begg[12] in Australia (who both studied under Angle) re-introduced dentistry extraction into orthodontics during the 1940s and 1950s so they could improve facial esthetics while also ensuring better stability concerning occlusal relationships.[13]

In the postwar period, cephalometric radiography[14] started to be used by orthodontists for measuring changes in tooth and jaw position caused by growth and treatment.[15] The x-rays showed that many Class II and III malocclusions were due to improper jaw relations as opposed to misaligned teeth. It became evident that orthodontic therapy could adjust mandibular development, leading to the formation of functional jaw orthopedics in Europe and extraoral force measures in the US. These days, both functional appliances and extraoral devices are applied around the globe with the aim of amending growth patterns and forms. Consequently, pursuing true, or at least improved, jaw relationships had become the main objective of treatment by the mid-20th century.[8]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, orthodontics was in need of an upgrade. The American Journal of Orthodontics was created for this purpose in 1915; before it, there were no scientific objectives to follow, nor any precise classification system and brackets that lacked features.[16]

Until the mid-1970s, braces were made by wrapping metal around each tooth.[9] With advancements in adhesives, it became possible to instead bond metal brackets to the teeth.[9]

In 1972, Lawrence F. Andrews gave an insightful definition of the ideal occlusion in permanent teeth. This has had meaningful effects on orthodontic treatments that are administered regularly,[16] and these are: 1. Correct interarchal relationships 2. Correct crown angulation (tip) 3. Correct crown inclination (torque) 4. No rotations 5. Tight contact points 6. Flat Curve of Spee (0.0–2.5 mm),[17] and based on these principles, he discovered a treatment system called the straight-wire appliance system, or the pre-adjusted edgewise system. Introduced in 1976, Larry Andrews' pre-adjusted edgewise appliance, more commonly known as the straight wire appliance, has since revolutionized fixed orthodontic treatment. The advantage of the design lies in its bracket and archwire combination, which requires only minimal wire bending from the orthodontist or clinician. It's aptly named after this feature: the angle of the slot and thickness of the bracket base ultimately determine where each tooth is situated with little need for extra manipulation.[18][19][20]

Prior to the invention of a straight wire appliance, orthodontists were utilizing a non-programmed standard edgewise fixed appliance system, or Begg's pin and tube system. Both of these systems employed identical brackets for each tooth and necessitated the bending of an archwire in three planes for locating teeth in their desired positions, with these bends dictating ultimate placements.[18]

Evolution of the current orthodontic appliances

[edit]

When it comes to orthodontic appliances, they are divided into two types: removable and fixed. Removable appliances can be taken on and off by the patient as required. On the other hand, fixed appliances cannot be taken off as they remain bonded to the teeth during treatment.

Fixed appliances

[edit]

Fixed orthodontic appliances are predominantly derived from the edgewise appliance approach, which typically begins with round wires before transitioning to rectangular archwires for improving tooth alignment. These rectangluar wires promote precision in the positioning of teeth following initial treatment. In contrast to the Begg appliance, which was based solely on round wires and auxiliary springs, the Tip-Edge system emerged in the early 21st century. This innovative technology allowed for the utilization of rectangular archwires to precisely control tooth movement during the finishing stages after initial treatment with round wires. Thus, almost all modern fixed appliances can be considered variations on this edgewise appliance system.

Early 20th-century orthodontist Edward Angle made a major contribution to the world of dentistry. He created four distinct appliance systems that have been used as the basis for many orthodontic treatments today, barring a few exceptions. They are E-arch, pin and tube, ribbon arch, and edgewise systems.

E-arch

[edit]

Edward H. Angle made a significant contribution to the dental field when he released the 7th edition of his book in 1907, which outlined his theories and detailed his technique. This approach was founded upon the iconic "E-Arch" or 'the-arch' shape as well as inter-maxillary elastics.[21] This device was different from any other appliance of its period as it featured a rigid framework to which teeth could be tied effectively in order to recreate an arch form that followed pre-defined dimensions.[22] Molars were fitted with braces, and a powerful labial archwire was positioned around the arch. The wire ended in a thread, and to move it forward, an adjustable nut was used, which allowed for an increase in circumference. By ligation, each individual tooth was attached to this expansive archwire.[8]

Pin and tube appliance

[edit]

Due to its limited range of motion, Angle was unable to achieve precise tooth positioning with an E-arch. In order to bypass this issue, he started using bands on other teeth combined with a vertical tube for each individual tooth. These tubes held a soldered pin, which could be repositioned at each appointment in order to move them in place.[8] Dubbed the "bone-growing appliance", this contraption was theorized to encourage healthier bone growth due to its potential for transferring force directly to the roots.[23] However, implementing it proved troublesome in reality.

Ribbon arch

[edit]

Realizing that the pin and tube appliance was not easy to control, Angle developed a better option, the ribbon arch, which was much simpler to use. Most of its components were already prepared by the manufacturer, so it was significantly easier to manage than before. In order to attach the ribbon arch, the occlusal area of the bracket was opened. Brackets were only added to eight incisors and mandibular canines, as it would be impossible to insert the arch into both horizontal molar tubes and the vertical brackets of adjacent premolars. This lack of understanding posed a considerable challenge to dental professionals; they were unable to make corrections to an excessive Spee curve in bicuspid teeth.[24] Despite the complexity of the situation, it was necessary for practitioners to find a resolution. Unparalleled to its counterparts, what made the ribbon arch instantly popular was that its archwire had remarkable spring qualities and could be utilized to accurately align teeth that were misaligned. However, a major drawback of this device was its inability to effectively control root position since it did not have enough resilience to generate the torque movements required for setting roots in their new place.[8]

Edgewise appliance

[edit]

In an effort to rectify the issues with the ribbon arch, Angle shifted the orientation of its slot from vertical, instead making it horizontal. In addition, he swapped out the wire and replaced it with a precious metal wire that was rotated by 90 degrees in relation—henceforth known as Edgewise.[25] Following extensive trials, it was concluded that dimensions of 22 × 28 mils were optimal for obtaining excellent control over crown and root positioning across all three planes of space.[26] After debuting in 1928, this appliance quickly became one of the mainstays for multibanded fixed therapy, although ribbon arches continued to be utilized for another decade or so beyond this point too.[8]

Labiolingual

[edit]

Prior to Angle, the idea of fitting attachments on individual teeth had not been thought of, and in his lifetime, his concern for precisely positioning each tooth was not highly appraised. In addition to using fingersprings for repositioning teeth with a range of removable devices, two main appliance systems were very popular in the early part of the 20th century. Labiolingual appliances use bands on the first molars joined with heavy lingual and labial archwires affixed with soldered fingersprings to shift single teeth.

Twin wire

[edit]

Utilizing bands around both incisors and molars, a twin-wire appliance was designed to provide alignment between these teeth. Constructed with two 10-mil steel archwires, its delicate features were safeguarded by lengthy tubes stretching from molars towards canines. Despite its efforts, it had limited capacity for movement without further modifications, rendering it obsolete in modern orthodontic practice.

Begg's Appliance

[edit]

Returning to Australia in the 1920s, the renowned orthodontist, Raymond Begg, applied his knowledge of ribbon arch appliances, which he had learned from the Angle School. On top of this, Begg recognized that extracting teeth was sometimes vital for successful outcomes and sought to modify the ribbon arch appliance to provide more control when dealing with root positioning. In the late 1930s, Begg developed his adaptation of the appliance, which took three forms. Firstly, a high-strength 16-mil round stainless steel wire replaced the original precious metal ribbon arch. Secondly, he kept the same ribbon arch bracket but inverted it so that it pointed toward the gums instead of away from them. Lastly, auxiliary springs were added to control root movement. This resulted in what would come to be known as the Begg Appliance. With this design, friction was decreased since contact between wire and bracket was minimal, and binding was minimized due to tipping and uprighting being used for anchorage control, which lessened contact angles between wires and corners of the bracket.

Tip-Edge System

[edit]

Begg's influence is still seen in modern appliances, such as Tip-Edge brackets. This type of bracket incorporates a rectangular slot cutaway on one side to allow for crown tipping with no incisal deflection of an archwire, allowing teeth to be tipped during space closure and then uprighted through auxiliary springs or even a rectangular wire for torque purposes in finishing. At the initial stages of treatment, small-diameter steel archwires should be used when working with Tip-Edge brackets.

Contemporary edgewise systems

[edit]

Throughout time, there has been a shift in which appliances are favored by dentists. In particular, during the 1960s, when it was introduced, the Begg appliance gained wide popularity due to its efficiency compared to edgewise appliances of that era; it could produce the same results with less investment on the dentist's part. Nevertheless, since then, there have been advances in technology and sophistication in edgewise appliances, which led to the opposite conclusion: nowadays, edgewise appliances are more efficient than the Begg appliance, thus explaining why it is commonly used.

Automatic rotational control

[edit]

At the beginning, Angle attached eyelets to the edges of archwires so that they could be held with ligatures and help manage rotations. Now, however, no extra ligature is needed due to either twin brackets or single brackets that have added wings touching underneath the wire (Lewis or Lang brackets). Both types of brackets simplify the process of obtaining moments that control movements along a particular plane of space.

Alteration in bracket slot dimensions

[edit]

In modern dentistry, two types of edgewise appliances exist: the 18- and 22-slot varieties. While these appliances are used differently, the introduction of a 20-slot device with more precise features has been considered but not pursued yet.[27]

Straight-wire bracket prescriptions

[edit]

Rather than rely on the same bracket for all teeth, L.F. Andrews found a way to make different brackets for each tooth in the 1980s, thanks to the increased convenience of bonding.[28] This adjustment enabled him to avoid having multiple bends in archwires that would have been needed to make up for variations in tooth anatomy. Ultimately, this led to what was termed a "straight-wire appliance" system – an edgewise appliance that greatly enhanced its efficiency.[29] The modern edgewise appliance has slightly different construction than the original one. Instead of relying on faciolingual bends to accommodate variations among teeth, each bracket has a correspondingly varying base thickness depending on the tooth it is intended for. However, due to individual differences between teeth, this does not completely eliminate the need for compensating bends.[30] Accurately placing the roots of many teeth requires angling brackets in relation to the long axis of the tooth. Traditionally, this mesiodistal root positioning necessitated using second-order, or tip, bends along the archwire. However, angling the bracket or bracket slot eliminates this need for bends.

Given the discrepancies in inclination of facial surfaces across individual teeth, placing a twist, otherwise known as third-order or torque bends, into segments of each rectangular archwire was initially required with the edgewise appliance. These bends were necessary for all patients and wires, not just to avoid any unintentional movement of suitably placed teeth or when moving roots facially or lingually. Angulation of either brackets or slots can minimize the need for second-order or tip bends on archwires. Contemporary edgewise appliances come with brackets designed to adjust for any facial inclinations, thereby eliminating or reducing any third-order bends. These brackets already have angulation and torque values built in so that each rectangluar archwire can be contorted to form a custom fit without inadvertently shifting any correctly positioned teeth. Without bracket angulation and torque, second-order or tip bends would still be required on each patient's archwire.

Methods

[edit]

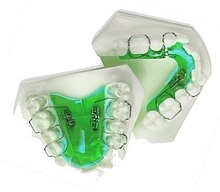

Upper and lower jaw functional expanders

Upper and lower jaw functional expanders

A typical treatment for incorrectly positioned teeth (malocclusion) takes from one to two years, with braces being adjusted every four to 10 weeks by orthodontists,[31] while university-trained dental specialists are versed in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of dental and facial irregularities. Orthodontists offer a wide range of treatment options to straighten crooked teeth, fix irregular bites, and align the jaws correctly.[32] There are many ways to adjust malocclusion. In growing patients, there are more options to treat skeletal discrepancies, either by promoting or restricting growth using functional appliances, orthodontic headgear, or a reverse pull facemask. Most orthodontic work begins in the early permanent dentition stage before skeletal growth is completed. If skeletal growth has completed, jaw surgery is an option. Sometimes teeth are extracted to aid the orthodontic treatment (teeth are extracted in about half of all the cases, most commonly the premolars).[33]

Orthodontic therapy may include the use of fixed or removable appliances. Most orthodontic therapy is delivered using appliances that are fixed in place,[34] for example, braces that are adhesively bonded to the teeth. Fixed appliances may provide greater mechanical control of the teeth; optimal treatment outcomes are improved by using fixed appliances.

Fixed appliances may be used, for example, to rotate teeth if they do not fit the arch shape of the other teeth in the mouth, to adjust multiple teeth to different places, to change the tooth angle of teeth, or to change the position of a tooth's root. This treatment course is not preferred where a patient has poor oral hygiene, as decalcification, tooth decay, or other complications may result. If a patient is unmotivated (insofar as treatment takes several months and requires commitment to oral hygiene), or if malocclusions are mild.

The biology of tooth movement and how advances in gene therapy and molecular biology technology may shape the future of orthodontic treatment.[35]

Braces

[edit]

Dental braces

Dental braces

Braces are usually placed on the front side of the teeth, but they may also be placed on the side facing the tongue (called lingual braces). Brackets made out of stainless steel or porcelain are bonded to the center of the teeth using an adhesive. Wires are placed in a slot in the brackets, which allows for controlled movement in all three dimensions.

Apart from wires, forces can be applied using elastic bands,[36] and springs may be used to push teeth apart or to close a gap. Several teeth may be tied together with ligatures, and different kinds of hooks can be placed to allow for connecting an elastic band.[37][36]

Clear aligners are an alternative to braces, but insufficient evidence exists to determine their effectiveness.[38]

Treatment duration

[edit]

The time required for braces varies from person to person as it depends on the severity of the problem, the amount of room available, the distance the teeth must travel, the health of the teeth, gums, and supporting bone, and how closely the patient follows instructions. On average, however, once the braces are put on, they usually remain in place for one to three years. After braces are removed, most patients will need to wear a retainer all the time for the first six months, then only during sleep for many years.[39]

Headgear

[edit]

Orthodontic headgear, sometimes referred to as an "extra-oral appliance", is a treatment approach that requires the patient to have a device strapped onto their head to help correct malocclusion—typically used when the teeth do not align properly. Headgear is most often used along with braces or other orthodontic appliances. While braces correct the position of teeth, orthodontic headgear—which, as the name suggests, is worn on or strapped onto the patient's head—is most often added to orthodontic treatment to help alter the alignment of the jaw, although there are some situations in which such an appliance can help move teeth, particularly molars.

Full orthodontic headgear with headcap, fitting straps, facebow, and elastics

Full orthodontic headgear with headcap, fitting straps, facebow, and elastics

Whatever the purpose, orthodontic headgear works by exerting tension on the braces via hooks, a facebow, coils, elastic bands, metal orthodontic bands, and other attachable appliances directly into the patient's mouth. It is most effective for children and teenagers because their jaws are still developing and can be easily manipulated. (If an adult is fitted with headgear, it is usually to help correct the position of teeth that have shifted after other teeth have been extracted.) Thus, headgear is typically used to treat a number of jaw alignment or bite problems, such as overbite and underbite.[40]

Palatal expansion

[edit]

Palatal expansion can be best achieved using a fixed tissue-borne appliance. Removable appliances can push teeth outward but are less effective at maxillary sutural expansion. The effects of a removable expander may look the same as they push teeth outward, but they should not be confused with actually expanding the palate. Proper palate expansion can create more space for teeth as well as improve both oral and nasal airflow.[41]

Jaw surgery

[edit]

Jaw surgery may be required to fix severe malocclusions.[42] The bone is broken during surgery and stabilized with titanium (or bioresorbable) plates and screws to allow for healing to take place.[43] After surgery, regular orthodontic treatment is used to move the teeth into their final position.[44]

During treatment

[edit]

To reduce pain during the orthodontic treatment, low-level laser therapy (LLLT), vibratory devices, chewing adjuncts, brainwave music, or cognitive behavioral therapy can be used. However, the supporting evidence is of low quality, and the results are inconclusive.[45]

Post treatment

[edit]

After orthodontic treatment has been completed, there is a tendency for teeth to return, or relapse, back to their pre-treatment positions. Over 50% of patients have some reversion to pre-treatment positions within 10 years following treatment.[46] To prevent relapse, the majority of patients will be offered a retainer once treatment has been completed and will benefit from wearing their retainers. Retainers can be either fixed or removable.

Removable retainers

[edit]

Removable retainers are made from clear plastic, and they are custom-fitted for the patient's mouth. It has a tight fit and holds all of the teeth in position. There are many types of brands for clear retainers, including Zendura Retainer, Essix Retainer, and Vivera Retainer.[47] A Hawley retainer is also a removable orthodontic appliance made from a combination of plastic and metal that is custom-molded to fit the patient's mouth. Removable retainers will be worn for different periods of time, depending on the patient's need to stabilize the dentition.[48]

Fixed retainers

[edit]

Fixed retainers are a simple wire fixed to the tongue-facing part of the incisors using dental adhesive and can be specifically useful to prevent rotation in incisors. Other types of fixed retainers can include labial or lingual braces, with brackets fixed to the teeth.[48]

Clear aligners

[edit]

Clear aligners are another form of orthodontics commonly used today, involving removable plastic trays. There has been controversy about the effectiveness of aligners such as Invisalign or Byte; some consider them to be faster and more freeing than the alternatives.[49]

Training

[edit]

There are several specialty areas in dentistry, but the specialty of orthodontics was the first to be recognized within dentistry.[50] Specifically, the American Dental Association recognized orthodontics as a specialty in the 1950s.[50] Each country has its own system for training and registering orthodontic specialists.

Australia

[edit]

In Australia, to obtain an accredited three-year full-time university degree in orthodontics, one will need to be a qualified dentist (complete an AHPRA-registered general dental degree) with a minimum of two years of clinical experience. There are several universities in Australia that offer orthodontic programs: the University of Adelaide, the University of Melbourne, the University of Sydney, the University of Queensland, the University of Western Australia, and the University of Otago.[51] Orthodontic courses are accredited by the Australian Dental Council and reviewed by the Australian Society of Orthodontists (ASO). Prospective applicants should obtain information from the relevant institution before applying for admission.[52] After completing a degree in orthodontics, specialists are required to be registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) in order to practice.[53][54]

Bangladesh

[edit]

Dhaka Dental College in Bangladesh is one of the many schools recognized by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council (BM&DC) that offer post-graduation orthodontic courses.[55][56] Before applying to any post-graduation training courses, an applicant must have completed the Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) examination from any dental college.[55] After application, the applicant must take an admissions test held by the specific college.[55] If successful, selected candidates undergo training for six months.[57]

Canada

[edit]

In Canada, obtaining a dental degree, such as a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) or Doctor of Medical Dentistry (DMD), would be required before being accepted by a school for orthodontic training.[58] Currently, there are 10 schools in the country offering the orthodontic specialty.[58] Candidates should contact the individual school directly to obtain the most recent pre-requisites before entry.[58] The Canadian Dental Association expects orthodontists to complete at least two years of post-doctoral, specialty training in orthodontics in an accredited program after graduating from their dental degree.

United States

[edit]

Similar to Canada, there are several colleges and universities in the United States that offer orthodontic programs. Every school has a different enrollment process, but every applicant is required to have graduated with a DDS or DMD from an accredited dental school.[59][60] Entrance into an accredited orthodontics program is extremely competitive and begins by passing a national or state licensing exam.[61]

The program generally lasts for two to three years, and by the final year, graduates are required to complete the written American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) exam.[61] This exam is also broken down into two components: a written exam and a clinical exam.[61] The written exam is a comprehensive exam that tests for the applicant's knowledge of basic sciences and clinical concepts.[61] The clinical exam, however, consists of a Board Case Oral Examination (BCOE), a Case Report Examination (CRE), and a Case Report Oral Examination (CROE).[61] Once certified, certification must then be renewed every ten years.[61] Orthodontic programs can award a Master of Science degree, a Doctor of Science degree, or a Doctor of Philosophy degree, depending on the school and individual research requirements.[62]

United Kingdom

[edit]

|

|

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.

Find sources: "Orthodontics" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2023)

|

Throughout the United Kingdom, there are several Orthodontic Specialty Training Registrar posts available.[63] The program is full-time for three years, and upon completion, trainees graduate with a degree at the Masters or Doctorate level.[63] Training may take place within hospital departments that are linked to recognized dental schools.[63] Obtaining a Certificate of Completion of Specialty Training (CCST) allows an orthodontic specialist to be registered under the General Dental Council (GDC).[63] An orthodontic specialist can provide care within a primary care setting, but to work at a hospital as an orthodontic consultant, higher-level training is further required as a post-CCST trainee.[63] To work within a university setting as an academic consultant, completing research toward obtaining a Ph.D. is also required.[63]

See also

[edit]

- Orthodontic technology

- Orthodontic indices

- List of orthodontic functional appliances

- Molar distalization

- Mouth breathing

- Obligate nasal breathing

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Also referred to as orthodontia

- ^ "Orthodontics" comes from the Greek orthos ('correct, straight') and -odont- ('tooth').[1]

References

[edit]